Research

Effect of Serial Procedures on Fluency in Jazz Improvisation: Can Serial “Killing” Be Taught?

OR

View Below:

Effect of Serial Procedures on Fluency in Jazz Improvisation: Can Serial “Killing” Be Taught?

Ray P. Zepeda

Author Note

No financial support was received for this research or the authorship of this article.

Correspondence concerning this article should be addressed to Cambridge-West Publishing, 2110 Artesia Boulevard, Suite B, Redondo Beach, CA 90278. E-mail: info@cambridgewestpublishing.com

Abstract

While jazz has been America’s greatest musical contribution in the last century, there is another system that emerged contemporaneously in Europe and then in the United States, namely, serialism. Despite serialism’s prominence in the American academy and the proliferation of jazz studies programs, the two realms have enjoyed few synergies. This study will examine adding other components of serialism such as rhythm and dynamics separately and, after a pre-test to establish the improviser’s facility with standard material, asking the participant to improvise first with the pitch constraints and then adding the others one at a time under expert, double-blind panel adjudication. To what extent can the tenets of serialism be imposed and still permit accomplished jazz improvisers to execute with the fluency typical of their improvisations on traditional harmony-based music, executing idiomatically-sound ideas confidently and purposefully in time and with note selection appropriate for the prevailing harmony? In order to determine if the conditions impacted participants’ improvisational fluency, a repeated measures ANOVA will be conducted. Descriptive statistics will be reported for participants across each condition. Principal among the expected findings are that (1) facility with jazz improvisation over standard material is highly correlative with serial improvisational fluency with pitch-class considerations, (2) serialization of dynamics and rhythm is impracticable in improvisation and, at best, enables only a stilted performance interfering with the swing feel, and (3) as such, the pedagogical approach would therefore be to first ensure students can improvise at high level on standard material and then, for only the best such students, extending the instruction to the serial pitch-class language.

Key terms: improvisational fluency, unordered collection

Effect of Serial Procedures on Fluency in Jazz Improvisation: Can Serial “Killing” Be Taught

This study is inspired by the work of America’s greatest exponent of serialism, Milton Babbitt, who himself had a jazz background and whose All Set for jazz ensemble (1957) showed that the 12-tone language does not, in and of itself, diminish the visceral and emotive qualities of any music. Though fully scored, it is a bona fide jazz piece meant to be heard and not just seen on a score. This study is not an attempt to keep serialism alive in America but rather an exploration into how the serial language can be re-imagined in a contemporary and distinctly American fashion, translating the language of jazz to serialism rather than the other way around.

The literature on pedagogical methods for jazz improvisation in tonal music with functional harmony or over modal music is voluminous with method books emerging in the 1960s and 1970s (Aebersold, 1967; Baker, 1969; Coker, 1970; McGhee, 1974). While jazz has been America’s greatest musical contribution in the last century, there is another system that emerged contemporaneously in Europe and then in the United States, namely, serialism. Despite serialism’s prominence in the American academy and the proliferation of jazz studies programs, the two realms have enjoyed few synergies. In the few cases where this has occurred, the results have found favor with audiences of experts and laypersons alike (Garasa, 2017). It may be therefore advantageous for improvisers to develop this skill set to add to their arsenal. It is notable that even serialists such as Stockhausen embraced indeterminacy, introducing the unforeseeable outcome of improvisation as a reaction to the orthodoxy of rationally-conceived serial music, more in line with the American and German avant garde of John Cage, Christian Wolf, and Earle Brown (Kutschke, 1999).

The mathematical nature of research in the area of music theory has led to preponderance of highly technical literature in the academy especially with regard to serial organization. Mead (1994) has distilled these notions as they relate specifically to the music of Milton Babbitt including the aforementioned All Set. In that piece, written for the 1957 Brandeis Music Festival which that year was a jazz festival, Babbitt (1957) employed all six of the all-combinatorial hexachords, hence the title, and asks that the eighth notes be swung which gives the solos, albeit written, an improvisatory feel. Lest the reader posit that such pre-compositional design obviates the need for creative selection, Mailman (2010) showed that Babbitt’s arrays, in fact, open up thousands of possibilities. Zepeda (1996) took the All Set idea one step further in his I Care If You Listen where there is actual jazz improvisation required. Just as Babbitt did in All Set, Zepeda used all six of the all-combinatorial source hexachords for this piece. During the swing section, players are called upon to improvise jazz over each hexachord and its complement (the entire aggregate). Each soloist takes six choruses, one over each aggregate, treating each trichord as an unordered collection. Furthermore, each aggregate employs a different trichord generator to create intervallic variety.

May (2003) has shown what factors in students’ backgrounds correlate strongly to improvisation scores across seven dimensions on very standard jazz material, namely, F blues and Satin Doll, and found self-evaluation and aural imitation ability to be the two best predictors. Smith (2009) validated a 14-point rubric for evaluating jazz improvisation with high reliability, again on very standard material – Bb blues and Killer Joe. Ciorba (2009) studied 102 high school students measuring improvisational achievement (dependent variable) versus seven independent variables with Self-Assessment and Motivation leading the way. Again, that study evaluated improvisation on very standard material, Bb blues and Satin Doll. O’Gallagher (2013) presented a comprehensive method specifically addressing the application of serial techniques to jazz improvisation using the trichord as the basis. Beato (2017) demonstrated how 12-tone rows can be expertly used in jazz improvisation, ‘comping, and composition as lines, chords, or polychords. Like Zepeda (1996), these latter two focused solely on the pitch class aspect of serialism.

To what extent can the tenets of serialism be imposed and still permit accomplished jazz improvisers to execute with the fluency typical of their improvisations on traditional harmony-based music? Improvisational fluency is defined here as the degree to which the improviser executes idiomatically-sound ideas confidently and purposefully in time and with note selection appropriate for the prevailing harmony (May, 2003). For this study, improvisational fluency is taken to evaluate, with the rules of serialism imposed, the degree to which the improviser still maintains a melodic flow executing idiomatic jazz ideas in time and with good note choice at a level consistent with his/her competency in conventional (traditional harmony-based) jazz improvisation.

Rather than considering improvisation as a reaction to serialism as noted by Kutschke (1999), this study looks at the integration of improvisation adding other components of serialism such as rhythm, dynamics, and articulation separately and, after a pre-test to establish the improviser’s facility with standard material, asking the improviser to improvise first with the pitch constraints and then adding the others one at a time under expert, double-blind panel adjudication. If “a skilled improviser in any tradition must be able to deal with the relevant elements of melody, rhythm, and harmony in a spontaneous and expressive manner” (Dobbins, 1980, pp. 38-39), why should serial jazz be excluded from the list of traditions? Unlike examples from the concert music world such as Stockhausen’s Zeitmasse (1956) and Pierre Boulez’s Improvisations II sur Mallarme (1957) wherein limited improvisation takes place within the context of strict composition (Hamilton, 1960), the tests in this study require full-blown jazz improvisation within a rigid serial context. The following research questions were therefore proposed:

- Can fluency in serial improvisation be predicted by a known or established level of artistry in traditional jazz improvisation?

- How much does the imposition of serial conditions impact improvisational fluency?

- Is idiomatic jazz improvisation tenable with any number of serial conditions and, if so, what pedagogical methods are indicated?

Method

The experimental research method will permit various independent variables as treatments (pitch class organization consisting of whole aggregate, hexachord only, and unordered trichords; rhythm serialization, and dynamic serialization) with expert qualitative “measuring” of the resultant fluency as a dependent variable. A finite set of pitch classes to be played in no particular order is an unordered collection. Such a set, three for this study, may be employed by the improviser in any order, usually to generate interest for the listener via motivic development. Whereas pitch class serialization is commonplace, this study looks at adding other components of serialism such as rhythm and dynamics separately and, after a pre-test to establish the improviser’s facility with standard material, asks the improviser to improvise first with the pitch constraints and then adding the others one at a time under expert double-blind panel adjudication.

An experimental methodology will be used. Performed improvisations of twelve participants will be recorded over several Saturday half-day sessions over a period of 4 months in a music studio in a large Western state in the U.S. Participants will be placed in separate rooms where the waiting soloists can be sequestered without hearing and being influenced by the soloist performing at the time, and where the engineer and judges can be in the control room which is not visible from the tracking room and vice versa thereby ensuring the anonymity required for the double-blind process. The same judges would adjudicate all of the performances.

Limitations likely to be encountered are studio availability and the availability of all three judges on the same days. Livestream, Facebook Live, or in vitro evaluation of the recordings only on the judges’ own time are the workarounds to be implemented. Each individual judge will be required however to experience every soloist the first time in the same fashion as hearing some performances on the large studio monitors and others on small built-in laptop speakers could bias a subjective perception. The judges will be given the evaluation sheets and the serial information in advance to allow them to become familiar with the sound of the rows so that they can evaluate whether the soloist is adhering to them in his/her improvisations. Judges will be permitted to take the evaluation sheets home and reference the recordings which will be password protected in Dropbox to further verify adherence using their home keyboards. Completed evaluations would be due in two months for statistical processing. Great care will be taken to ensure recordings of all performances are de-identified. The study shall include no minors or intermediate-level or vulnerable adults for whom a musical challenge of this difficulty could be unduly stressful.

Participants

The twelve participants shall be accomplished jazz soloists. A pre-recorded rhythm section performing an excerpt from I Care If You Listen, a 12-tone piece by Ray Zepeda from his Re-Imagining Milton Babbitt album, shall consist of the five players from the album. Participant soloists will range from 23 to 70 years old including 11 males and 1 female comprised of 1 African-American male (upper-middle class), 1 Hispanic male (upper-middle class), 1 White male (upper-middle class), 6 White males (middle class), 1 Asian male (middle-class), 1 White female (middle class), and 1 White male (lower-middle class). Among the participants will be 3 saxophonists, 3 pianists, 2 trumpeters, 1 trombonist, 1 guitarist, 1 vibraphonist, and 1 double-bassist. This is a convenience sampling of artists whose playing I know. Only those who had proven facility with improvisation on standard material such that a baseline could be established with the pretest will be selected with a preference for those who at least had some knowledge of 12-tone music.

Instrumentation

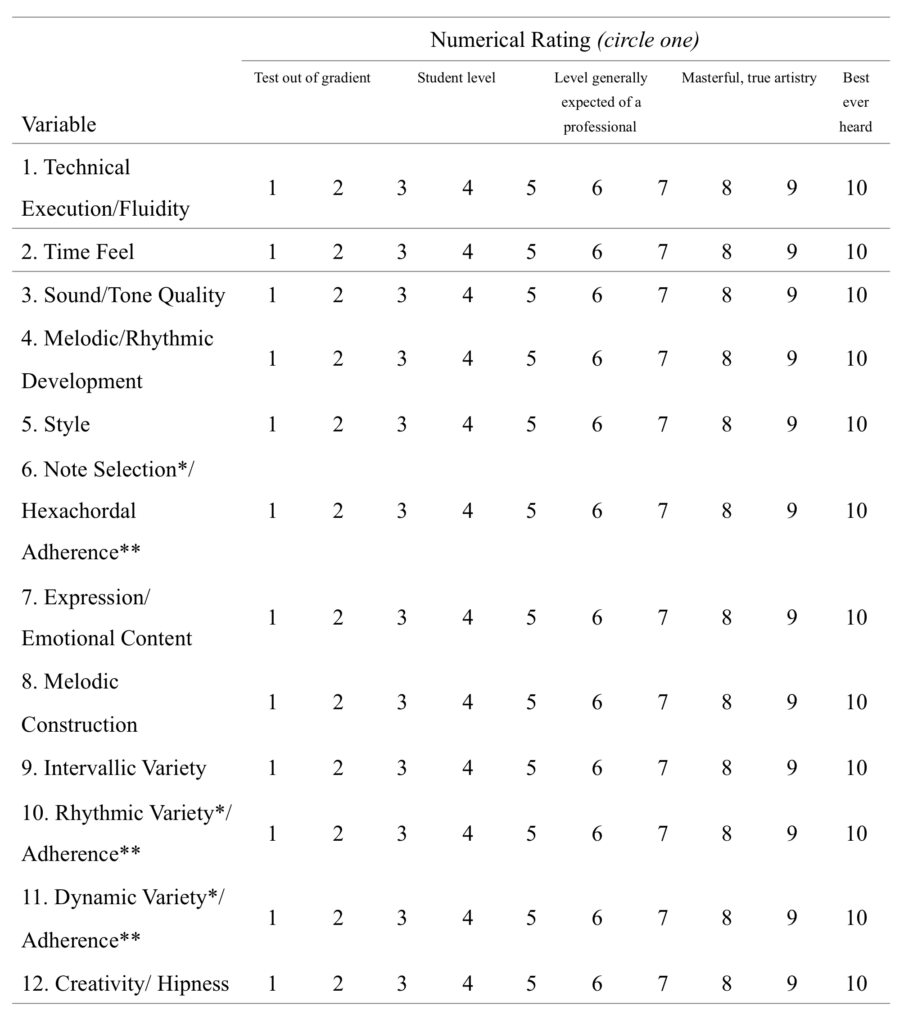

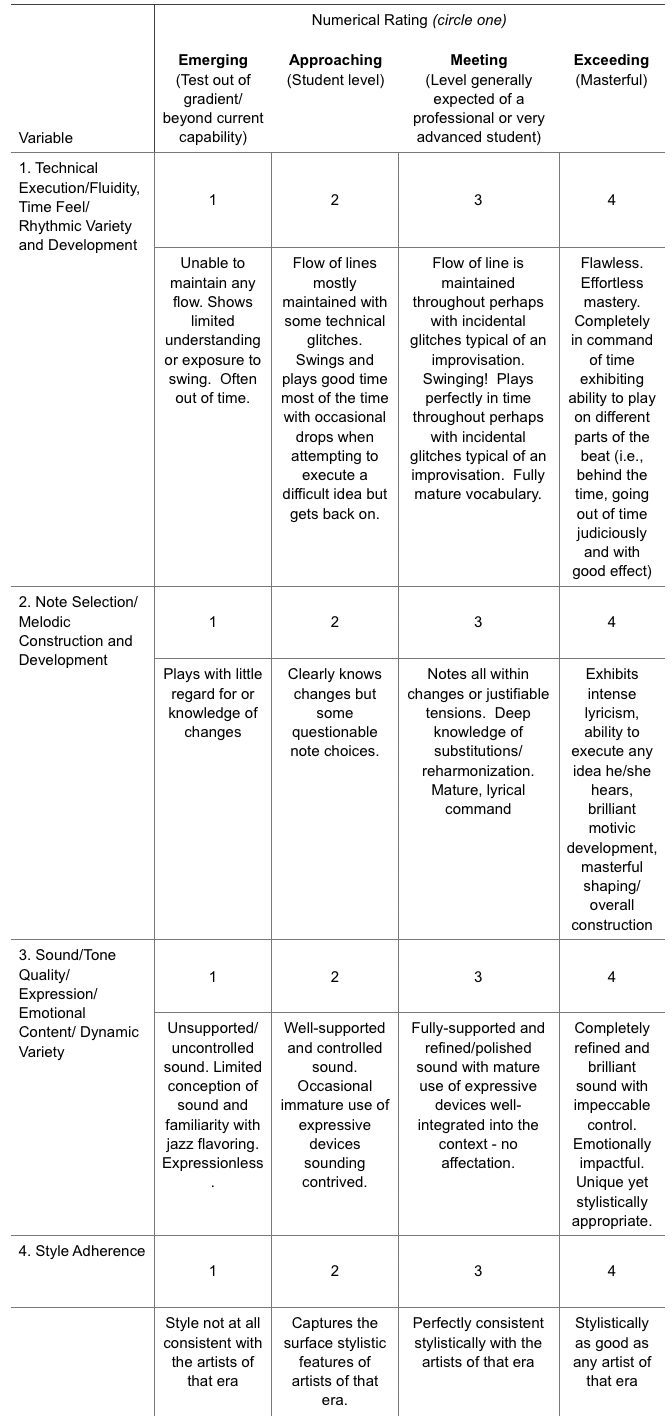

The primary instrument used for this study is an observation scale adjudication questionnaire to be completed by known experts in the area of jazz improvisation that will be developed based on the 7-point and 14-point instruments employed by May (2003) and Smith (2009) respectively. Both instruments resulted in high reliability coefficients in their respective studies. My emendations and modifications tailored these criteria to what can reasonably be expected from an improviser operating under the restrictions of serialism. This instrument will assess improvisational mastery/artistry based on subjective ratings and will contain twelve (12) items including most of the May (2003) items plus some of my own related to adherence to the serial structure.

Table 1

Improvisation Evaluation Scale: Traditional*/ Serial Jazz**

Design

For each soloist: Pre-test of 3 choruses over 3 jazz standards of the soloist’s own choosing with a live rhythm section or an Aebersold. Averaged scores on each dimension for each judge count. Solos over 72 measures (6 choruses) of the same pre-recorded excerpt from I Care If You Listen by Ray Zepeda (band with pre-recorded soloist muted): Serial improvisation considering pitch class only, 3 attempts, best scores from each judge count. Serial improvisation considering pitch class and dynamics and rhythm (attack point), 3 attempts, best scores from each judge count. Serial improvisation considering pitch class and dynamics, 3 attempts, best scores from each judge count.

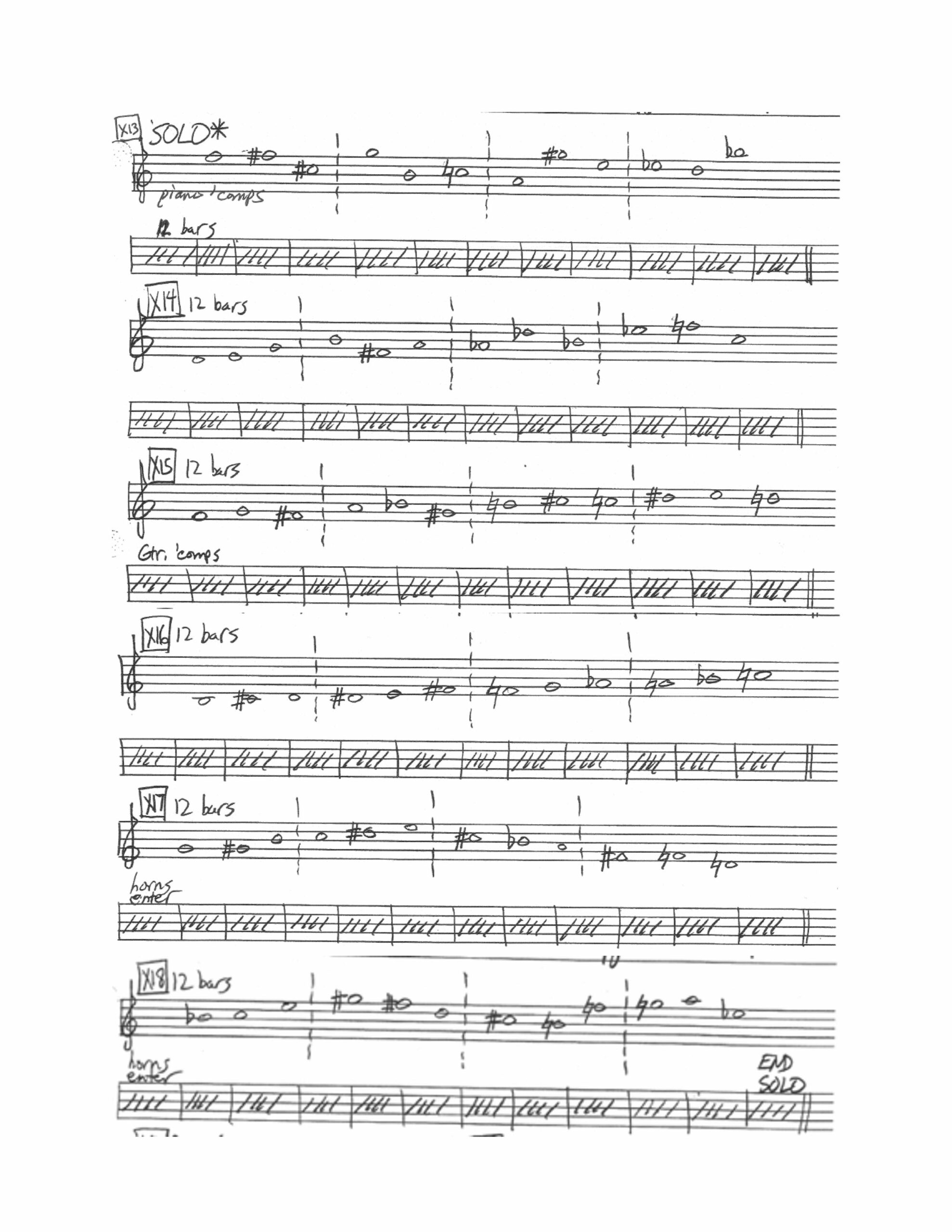

In the context of the piece, the improvised solo section takes up the bulk of the time and occupies the entire middle and latter sections. After a slow introduction featuring virtuosic flute writing, a fast pointillistic section ensues before, just as in Babbitt’s All Set, the percussion instruments enter as a “canon follower” playing the same rhythms as the composite ensemble rhythm for this section and leading into the solos. The soloists’ instructions are to “Play idiomatically in a jazz style, either “straight-ahead” bebop or “OUT” (Dolphy, Cecil Taylor, Ornette, Braxton, Ayler, etc.) You may vary the ordering of the pitch classes within each trichord but please play all three before moving on to the next trichord. Although you should normally play each note once, you may repeat a note several times or loop a motivic cell (even if it traverses the trichord demarcation line) without destroying the essential nature of the row. You also have the option of staying within a trichord for awhile, exploring every possible permutation of it if you wish. You are not obligated to complete the entire row a whole number of times within the allotted 12 measures though you should try to loop through it at least once. When it is time to move on to the next 12-bar section, you must commence soloing over the aggregate for that section (in the manner described above) regardless of where you were in the aggregate for the previous section. Pitch classes, by definition, may be played in any octave. Multiphonics and chords/clusters are permissible.” (Zepeda, 1996). The participant soloist’s part for the serial improvisation test – an excerpt from the actual vibraphone part – is shown below in Figure 1. Transposing and bass clef instruments will be given appropriately transposed parts.

Figure 1. Participant pitch-class prompt for serial improvisation test. Adapted from “I Care If You Listen”, by R. Zepeda, 1996, pp. 29-37. Copyright 1996 by Cambridge-West.

The 12 dynamic values to be considered by the participant in the pitch-class + dynamics test are 0) ppppp, 1) pppp, 2) ppp, 3) pp, 4) p, 5) mp, 6) mf, 7) f, 8) ff, 9) fff, 10) ffff, and 11) fffff.

For the rhythmic considerations, an idiomatic jazz approach is taken rather than the purely temporal duration or attack point method of organization characteristic of serious music. This accomplishes three things – (1) avoidance of the impossible mental task of executing the latter in a fast-tempo improvisational situation while (2) preserving serialism’s core principal of “maximal diversity” and (3) improving the chances of a jazz-like outcome. To this end, twelve rhythmic cells of one to four beats commonplace in jazz were chosen roughly in descending order of attack point speed: 0) 16th-note sextuplet, 1) two 16ths or a 16th followed by a dotted 8th, 2) four 16th notes, 3) 8th-note triplet, 4) two or four 8th-notes, 5) 8th-note/quarter note/8th note or two 8th-notes/8th-rest/8th-note, 6) quarter-note, 7) dotted quarter-note, 8) quarter-note triplet, 9) half-note, 10) dotted half-note, and 11) whole note.

The pre-recorded “harmonic” milieu over which the improvisation will occur is given below in Fig. 2 showing the ‘comping instrument pitch classes and the underlying bass line driven by a drummer playing contemporary jazz swing time punctuated with horn section background figures (not shown). The bass line is a linear statement of the source hexachord while the ‘comping instruments are limited to the pitch classes of its complement. The solo backgrounds too are limited to the prevailing aggregate. The instructions to the ‘comping instruments were simply that “’comping may incorporate chords/clusters and/or single notes. Formulate voicings and/or lines from the six pitch classes indicated for each section. Any octave is permitted for every note. The ordering is free but please play all six pitch classes before repeating any one.” (Zepeda, 1996).

Figure 2. Rhythm section accompaniment for serial improvisation test. Adapted from “I Care If You Listen”, by R. Zepeda, 1996, pp. 29-37. Copyright 1996 by Cambridge-West.

After the solos, the piece closes with a drum solo with flute accompaniment wherein the flutist is asked to improvise an accompaniment using the aforementioned six aggregates while interacting with the drummer.

Test Performance

In a double-blind process, three expert judges will score each soloist’s improvisation over the same passage across ten dimensions on a scale from 1 to 10. Each soloist will get three attempts at each of the following: (1) pitch only, (2) pitch + dynamics, and (3) pitch + dynamics + rhythm. For each judge, the highest score of each dimension will be taken, even if the scores are from different attempts, for each of the three evaluations – (1), (2), and (3). Each soloist will therefore give nine performances over the same passage of 72 measures at 216 bpm. (The “practice” threat to internal validity is intentional here as the idea is to really gauge the player’s maximum capability.) The mean and standard deviation from all of the judges for each condition will be tabulated and presented.

The major opportunities for risk mitigation include (1) soloist fatigue [9 choruses of standard jazz followed by 9 performances (6 choruses each) of progressively difficult serial jazz]. One possible mitigation would be to have players perform their standard set and then go back to the end of line while the others do theirs and then perform their serial set when their turn comes again. (2) Also, soloists’ interaction with the rhythm section on the serial treatments will be one-way only since the excerpt is pre-recorded. (3) For the pre-test, the lack of availability of the same exact rhythm section for every soloist is an internal validity threat. The mitigation of using Aebersolds would also create a one-way situation with regard to rhythm section interaction. This proviso will be made clear in the interpretation of results wherein rhythm section interaction is measured. One could raise the concern that each soloist having different pre-test material is an internal validity threat. This is by design, however, as the purpose is to establish the player’s maximum potential with standard jazz. Judges routinely make adjustments in consideration of quality vis a vis degree of difficulty. (4) With regard to privacy, many soloists will be at a sufficiently high level so as to make their playing, by virtue of its quality and uniqueness, potentially identifiable to a judge with expertise in this area. A non-disclosure agreement is one suggested mitigation.

Data Analysis and Presentation Methodology

There are two principal components of this:

1.) Analysis of data to confirm or disprove that improvisational mastery over standard jazz is correlative of same in serial jazz.

2.) Analysis of data to show degradation in improvisation as more serial treatments are added.

For the baseline pre-tests over standard jazz, the scores across each of the 10 dimensions for all 3 tunes would be averaged for each judge. An average of all the judges’ scores for that dimension would, in turn, be averaged but this time with the standard deviation (SD) reported. Each subject would therefore have 10 composite averages, one for each dimension. With each dimension equally weighted, these 10 composite averages can in turn be averaged to give a weighted average or a single-number reduction to that subject’s standard jazz improvisation baseline.

The same would be done with the tests imposing the 3 serial conditions: x = pitch-class consideration only, y = pitch-class and dynamic consideration, and z = pitch-class and dynamic and rhythm considerations consisting of 3 “takes” each, the only difference being that only the best scores for each dimension would be used regardless of which take that highest score was drawn from. For each treatment, each subject would therefore have their 10 high scores for each judge averaged to give a composite average for each dimension. With each dimension equally weighted, these 10 composite averages can in turn be averaged to give a weighted average or a single-number reduction to that subject’s serial jazz improvisation for that treatment. All of this would be repeated for the other two treatments.

In order to determine if the conditions impacted participants’ improvisational fluency, a repeated measures ANOVA will be conducted. Descriptive statistics will also be reported for participants across each condition.

Results

The baseline weighted average (also reporting SD) would then be compared to the weighted averages of x, y, and z (also reporting SD) and then using Pearson’s r to illustrate how well serial improvisational fluency can be predicted by standard jazz improvisational mastery, the latter of which is generally acquired by well-established pedagogical and experiential methods. If x shows a strong correlation, this would suggest that the way to teach serial improvisation is to first ensure mastery in standard jazz improvisation. (It may turn out, however, that the bar for executing y and z is so high that there will be little or no correlation to the standard jazz improvisation baseline). Or, we may be surprised to find that the best serial improvisers happened to have the lower baselines because, unlike in standard jazz improvisation, the pitches in serial jazz are written out in order. (This, however, would not be the hypothesis going in!)

Within the serial realm, the composite averages of x, y, and z (also reporting SD) would be compared to see which dimensions are most affected, presumably adversely, in going from x to y to z. The weighted averages of x, y, and z would also be compared using a repeated-measures ANOVA and a conclusion could be drawn as to whether jazz improvisation considering more than x is even tenable assuming the desired result is a performance recognizable as “jazz”. If not, then composers would be well served to refrain from such demands on professional performers let alone students. These data would be illustrated in several tables, graphs, and histograms.

Discussion and Implications

A conclusion would be drawn on how to best teach serial improvisation at the college or advanced high school level. Based on how these professionals perform, is it reasonable to add the restrictions of dynamics and rhythm or is even pitch too difficult for students? Is improvisational artistry on standard jazz material, as established by a pre-test, a reliable predictor of improvisational fluency under imposed serial treatments. To what extent do serial restrictions beyond pitch class organization affect fluency?

This study seeks to generalize the results to avant garde or contemporary straight-ahead jazz musicians and free jazz improvisers. This population would be well-served to adopt this skill set either to add flavor over chord changes or to add a measure of order to their improvisations which may appear random or solely gestural/textural. Further ecologically valid generalizations can extend to contemporary straight-ahead jazz or fusion where the chord changes are not so much functional as they are in a Great American Songbook standard but, rather, colors such that 12-tone shapes can be played without sounding “wrong”. It would also be generalizable to modal jazz where a strict adherence to the notes within the prevailing mode or to pentatonic patterns would grow tiresome over time (Beato, 2017).

References

Babbitt, M. (1957). All set. New York, NY: G. Schirmer.

Baker, D. (1969). Jazz improvisation: A comprehensive method of study for all players. Chicago, IL: DB Music Workshop.

Beato, R. (2017, January 9). Twelve tone triads: How to use tone rows in your soloing [Video]. Retrieved from https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=VvCkynymUDQ

Ciorba, C. (2009). Predicting Jazz Improvisation Achievement through the Creation of a Path-Analytical Model. Bulletin of the Council for Research in Music Education, (180), 43-57.

Coker, J., Casale, J., Campbell, G., & Greene, J. (1970). Patterns for jazz. Miami, FL: Studio P/R.

Dobbins, B. (1980). Improvisation: An Essential Element of Musical Proficiency. Music Educators Journal, 66(5), 36-41.

Garasa, C. (2017, October 4). A different kind of Bakersfield sound with new releases. The Californian. Retrieved from https://www.bakersfield.com/entertainment/music/

Hamilton, I. (1960). Serial Composition Today. Tempo, (55/56), 8-12.

Kutschke, B. (1999). Improvisation: An Always-Accessible Instrument of Innovation. Perspectives of New Music, 37(2), 147-162. doi:10.2307/833513

Mailman, J. (2010). Temporal dynamic form in music: Atonal, tonal, and other. (Doctoral dissertation, Eastman School of Music). Retrieved from http://www.joshuabanksmailman.com/index.html

May, L. (2003). Factors and Abilities Influencing Achievement in Instrumental Jazz Improvisation. Journal of Research in Music Education, 51, 245-258.

Mead, A. (1994). An introduction to the music of Milton Babbitt. Princeton, NY: Princeton University Press.

O’Gallagher, J. (2013). Twelve-tone improvisation: A method for using tone rows in jazz. Rottenburg, Germany: Advance Music.

Smith, D. (2009). Development and Validation of a Rating Scale for Wind Jazz Improvisation Performance. Journal of Research in Music Education, 57, 217-235.

Zepeda, R. (1996). I care if you listen: A critic’s response to just artistry. Redondo Beach, CA: Cambridge-West.

Mother’s Day Lessons from Our Elders

JAZZ IMPROVISATION ACROSS TRADITIONAL AND MODERN STYLES: ASSESSMENTS IN A SIX-WEEK UNIT WITHIN A UNIVERSITY-LEVEL JAZZ IMPROVISATION COURSE

Ray P. Zepeda

Happy Mother’s Day to all! While we spend this special day honoring our good mothers for their unconditional love, wisdom, and guidance, allow me to offer this introduction to my upcoming four-part educational blog on how to impart the wisdom and guidance of the masters to turn your students into bad mothers in their own right, if you know what I mean!

It is often said that, early in life, our peers are our most influential teachers, and that it is only later in life that we discover our parents, especially our mothers, had all the real answers. So too is it with our development as jazz improvisers. Content to study the artists of our own age, we often fail to reach deeper levels of expression due to our lack of understanding of where our contemporary mentors derived their influences from. It is only after this investigation into the improvisational styles of the masters of previous generations that our solos can exhibit maturity, authenticity, and range. The premise of the Unit is that such investigation must not stop at listening. Assimilation of the past must necessarily involve tactile reinforcement and must also engage both the eye and the ear. (Yes, I am talking about, dare I say, emulation.) The learning activities set forth in this Unit are designed to do just that. Contemporary players who continue to eschew such study are doomed to sound out of place in traditional jazz and swing settings thereby limiting their employability.

Unit Overview and Objectives for Jazz Improvisation Across Traditional and Modern Styles

Unit Objectives, Description, and Content Standards

Objective

The objective of this unit is for the student to achieve fluency across jazz styles, experiencing and gaining a deeper understanding of the lineage of the jazz language through introspection and assimilation. The student will be able to improvise convincingly and authentically in one modern and one traditional jazz style.

Content Standards

Responding:

The student will transcribe one chorus of an improvised jazz solo in a Traditional style and one in a Modern style of their choosing using appropriate notation for melody, rhythms, and articulations.

Connecting:

The student will be able to compare features of both jazz styles as they evolved through time and discuss the sociopolitical climate existing during each period.

Performing:

The student will perform both transcriptions.

Creating:

The student will improvise a solo in both styles on tunes of their choosing.

Desired Outcomes

Overarching Understandings to be Gained:

There are specific nuances peculiar to each historical style of jazz. Deliberately playing earlier styles with a modern conception is not only unprofessional but indicative of narcissism.

Improvisation and “swing” are learned skills buoyed by attitude, dogged persistence, constant listening, an open heart, and a humble spirit.

Misconceptions to Disavow:

Learning older styles connotes an adherence to the past and treats jazz as a museum. Introducing Third Stream elements is not so much an innovation but rather an “anti-jazz” Europeanization of the art form. The transition of jazz from a low-brow dancer’s music to a listener’s music elevated the art form to its rightful place in elite society.

It is pedagogically sufficient and valid to just say “go listen to Charlie Parker!”

Knowledge:

The student will know the “A” section, Bridge, AABA and other forms, all chords with stylistically-appropriate extensions/tensions, the historical context of each tune, voice-leading resolutions.

Skills to Acquire or Further Develop:

Playing, creating, improvising, listening, leadership behaviors, comparing, analyzing, researching, emulating while defining one’s own voice and artistic vision.

Essential Questions to Ponder and Reflect Upon:

Comparing swing-era soloists to those of the bebop and modern eras, how is it that the former were able to be so impactful with so little? Or, is what they were doing, in fact, “little”, given how “out of place” most modern artists sound when attempting to “cop” earlier styles?

Much has been written about how jazz has shaped popular culture. In what ways has popular culture shaped jazz?

Assessment Description: Performance Task

Goal:

Fluency and understanding across jazz styles.

Audience:

University/Conservatory students – primarily Music majors most of whom are Jazz Studies majors, some “non-traditional” community professionals.

Product/Performance:

Two (2) partial transcriptions and performances, two (2) improvised solos. Student to discuss reasoning for choices.

Standards:

A successful result will exhibit mastery in and internalization of two established jazz styles.

Learning Plan

Where do we go from here?:

To experience and gain a deeper understanding of the lineage of the jazz language, how it is transferred from generation to generation, the students will be asked the following: “Who did your favorite player study? Who did that player study? And so on back the birth of jazz. Then, describe your own style within this historical context. Who are your influences and what did you take from each of them? How will you continue to develop your own voice and, once you do, how would future generations describe you? An essay question assessing this understanding could appear on the Unit Exam.”

As students take gigs in either of the two chosen styles, encourage them to record themselves on that gig and objectively assess at least a day later how “authentic” they sound in that context.

Hooking the students in at the outset:

Jamming to original recordings of different jazz styles – creating while emulating established artists – rather than with Aebersold play-alongs. Students will enjoy playing along with and interacting (using fills and call-and-response) with the original soloist.

Experience/Explore:

In-class performances, historical jazz videos, independent research.

Exhibit/Self-Evaluate:

The student’s selection of the two styles and the artists whose solos they choose to transcribe will require introspection and an inventory of their pre-existing skill set and propensities. Feedback in Formative Assessments, particularly in the Comments section, will include actionable suggestions against which the student can self-monitor their progress. Moreover, the student will be encouraged to record their practice sessions to assess themselves objectively as they progress.

Tailoring:

The students will self-tailor it by choosing the styles, transcription sources, and tunes germane to themselves.

Learning Activities for Jazz Improvisation Across Traditional and Modern Styles

Learning Timeline

Learning Objective

The objective of this unit is for the student to achieve fluency across jazz styles, experiencing and gaining a deeper understanding of the lineage of the jazz language through introspection and assimilation. The student will be able to improvise convincingly and authentically in one modern and one traditional jazz style.

Methods

The primary vehicle for this Styles unit is jamming to original recordings of different jazz styles – creating while emulating established artists. This class will not involve Jamey Aebersold play-alongs. Rather, students will play along with and interacting (using fills and call-and-response) with the actual original soloist.

Unit Timeframe

This Styles unit within a semester-long Jazz Improvisation course will take six (6) weeks ending with a Unit Final Exam in Week 6.

Unit Schedule

Week 1:

- Introduction / Unit Overview

- Student selection of two jazz styles – one Traditional and one Modern

- Guidelines/Rubric for Transcriptions

- Guidelines/Rubric for Performance Assessments

- View portions of historical jazz videos. Style-related class discussion.

- Individual practice with recordings from YouTube using students’ individual devices with Professor walking around listening and providing formative feedback and suggestions on how to practice Styles. Original recording should be ambiently audible at low volume.

- Assigned reading and listening. Unit Final Exam in part will draw from these.

Week 2:

- Survey the class on Student selections of jazz styles

- Round-robin improvisations on each of the styles using recordings that students bring in, 1 to 3 choruses each.

- Instructor and Peer Feedback

- View portions of historical jazz videos. Style-related class discussion.

- Individual practice with recordings of student-selected styles from YouTube or recordings using students’ individual devices with Professor walking around listening and providing formative feedback. Original recording should be ambiently audible at low volume.

- Assigned reading and listening

Week 3:

- Class discussion on Styles chosen and artists whose solos students have selected to transcribe. Be prepared to discuss reasons for selections and historical context. What can you say about your two artists’ styles?

- Round-robin improvisations on each students two styles using recordings that students bring in, 1 to 3 choruses each.

- Instructor and Peer Feedback

- View portions of historical jazz videos, Style-related class discussion.

- Individual practice with recordings from YouTube with Professor walking around listening and providing formative feedback. Original recording should be ambiently audible at low volume.

- Assigned reading and listening

Week 4:

- Class discussion on tunes chosen. Be prepared to discuss reasons for selections and historical context

- Round-robin warm-up improvisations on each student’s two styles using recordings that students bring in – 1 to 3 choruses each.

- Instructor and Peer Feedback

- Summative Assessments of student performances of 3 choruses of each of his/her two styles on tunes of their choosing using either a recording with the original artist’s solo muted or a rhythm section from within the class. For the latter option have lead sheets available to distribute if not a common standard tune.

- Instructor and Peer Feedback

- Assigned reading and listening

Week 5:

- Class presentations/performances of solo transcriptions of one chorus in each of the two styles. Each student will:

- Have their handwritten transcription on the overhead for the class to see

- Discuss with the class their artist and their style highlighting details about the original recording and technical details in transcription.

- Play the original recording for the class

- Perform the solo transcription a cappella or with the original recording at low volume

- Repeat for Style #2

- Assigned reading and listening

Week 6: Unit Final Exam (90 minutes)

- 10 multiple choice questions (1 point each)

- 10 fill-in-the-blank questions (1point each)

- 10 True-False questions (1 point each)

- 8 Matching questions (1 point each)

- 1 half-page essay question (12 points)

- 2 full-page essay questions (25 points each)

Memorial Day Thoughts on America’s Music

JAZZ IMPROVISATION ACROSS TRADITIONAL AND MODERN STYLES: ASSESSMENTS IN A SIX-WEEK UNIT WITHIN A UNIVERSITY-LEVEL JAZZ IMPROVISATION COURSE

PART 1 OF 4: FORMATIVE ASSESSMENT – FLUIDITY AND MELODIC CONSTRUCTION

Ray P. Zepeda

Two weeks ago, I offered an introduction to a four-part educational blog on this subject of which this is the first. Formative assessments should be done on a continuous basis providing feedback on various and sundry elements of jazz improvisation in the case of this class. This example isolates just two such elements, fluidity and melodic construction. Future parts of this blog shall deal with other elements of improvisation.

While the art dilettanti look upon the judgement of artistic merit with suspicion, many critics have no issue with it but too often ascribe greatness to the technically questionable and offer only derision towards those of sound, traditional grounding and who exhibit instrumental mastery. Is it any wonder students often look upon testing with a degree of trepidation, conflicted and not knowing what is expected of them as they read jazz publications and other media covering art? It is therefore critical that a clear and detailed rubric be presented as a basis for assessment. Rosenberg (1967) asserts that quality of art is objectively traceable to commonly agreed-upon standards of the masters tempered by individual subjective response. Both objective and subjective measures are given adequate representation in these rubrics.

As we go forth today and honor those who “gave their last full measure of devotion” (Lincoln, 1863), let us also remember that it was their sacrifice that preserved our freedom to create and play this form of music, born of America’s original sin yet celebrated in her devotion to the struggle to atone for it, and that they faced tests much greater than any that will be encountered in this class or on any bandstand, and with much higher stakes.

Wishing you and yours a blessed and meaningful Memorial Day holiday.

Rubric

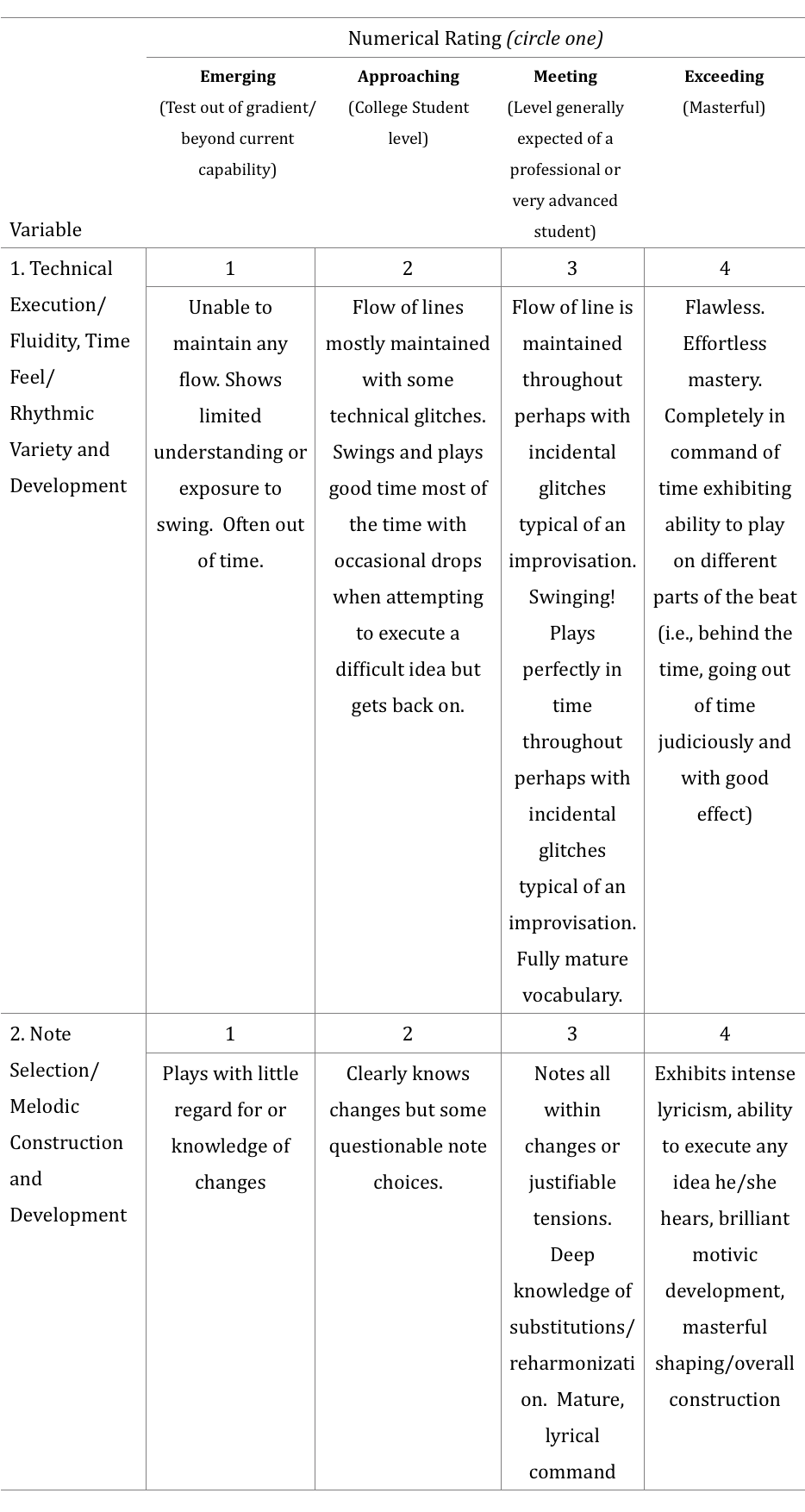

Performance Assessment

In other Formative Assessments throughout this Unit, I have scored each chorus of each soloist’s improvisation across the Sound/ Expression dimension and the Style Adherence dimension on a scale from 1 to 4. This Formative Assessment will focus on the Technical Execution/Fluidity, Time Feel/Rhythmic Variety and Development, and Note Selection/Melodic Construction and Development dimensions. Each soloist will get three choruses of each of the following: (1) a Traditional style (2) a Modern style, both of the soloist’s choosing, over a tune of the soloist’s choosing. You may use a rhythm section from the class or, for the more technologically savvy amongst you, the original recording with the soloist muted. The objective is that the student will be able to perform convincingly in both styles, exhibiting all the nuances and characteristics typical of that era.

Traditional styles: Ragtime, Dixieland/Trad. Jazz, Early to Late Swing, Early R&B, etc.

Modern styles: Bebop, Hard Bop, West Coast/Cool, Post Bop, Modal Jazz, Progressive Jazz/Third Stream, Fusion, Contemporary/Smooth Jazz, etc.

The highest chorus score of each solo will be taken for each of the evaluations – (1) and (2). Each soloist will therefore play six total choruses.

Table 1

Improvisation Evaluation Scale: Traditional / Modern Jazz [adapted in part from Smith (2009)]

Comments:

Feedback from Scale Assessment:

3 and above: Exhibits or exemplifies the parameter or characteristic nearly perfectly throughout

2: Exhibits the parameter or characteristic moderately or mostly throughout

1: Does not exhibit the parameter or characteristic to any measureable degree

References

Lincoln, A. (2020). The Gettysburg address [Transcript]. Retrieved from http://www.abrahamlincolnonline.org/lincoln/speeches/gettysburg.htm

Rosenberg, J. (1967). On Quality In Art: Criteria of Excellence, Past and Present. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University.

Smith, D. (2009). Development and Validation of a Rating Scale for Wind Jazz Improvisation Performance. Journal of Research in Music Education, 57, 217-235.

Fathers as Role Models – Emulating the Masters

JAZZ IMPROVISATION ACROSS TRADITIONAL AND MODERN STYLES: ASSESSMENTS IN A SIX-WEEK UNIT WITHIN A UNIVERSITY-LEVEL JAZZ IMPROVISATION COURSE

PART 2 OF 4: FORMATIVE ASSESSMENT – SOUND, EXPRESSION, STYLE

Fathers as Role Models – Emulating the Masters

Ray P. Zepeda

Last month, I offered a sobering Memorial Day tribute to those whose sacrifice preserved our freedom to create and play this form of music sometimes referred to as “America’s classical music.” For this second of four installments, I would like to center the discourse around a different but related type of respect, one that still holds the object of veneration up as a heroic figure in the observer’s estimation but which ultimately derives its gravitas from repeated direct and personal interactions, is experientially based, and is decidedly more formative.

Admittedly, it is almost never intentional that we as young men end up becoming our fathers. How many times did we as young boys steel ourselves with the affirmation that it would never be so? Yet, if we were to be completely honest with ourselves, it is the daily observation of behaviors, both beneficial and deleterious, in response to life situations that formed the basis of how we negotiate our adult lives because we, perhaps subconsciously, perhaps not, saw the payoffs of such actions, some of which may be temporary solutions that prove destructive in the long term, others which may set us on the righteous path.

Our formative years as jazz improvisers are not too different and are, in most cases, even more deliberately emulative. Artists and genres that speak to us most directly during these years tend to have the greatest influence on our playing throughout our careers, of course, not that one cannot assimilate other styles later in life as often happens. Rare is the unstudied sui generis iconoclast that contributes anything beyond eccentricity and then assumes a place of importance. The ones seemingly fitting of that description often belie an early life of structured pedagogy and conventional influences upon further investigation.

It would therefore be folly for any developing improviser today to eschew such detailed study of the masters. John Madden or Yogi Berra might say, “If you don’t sound like anything, you don’t sound like anything.” In other words, anyone can sound like nobody if nobody would want to sound like they do. Emulative study is neither imitation nor evidence of a paucity of invention. Even a deliberate attempt to imitate certain artists will result in your own unique distillation of these masters with the underpinning of their collective craft. Regurgitation of isolated licks from a master’s solo transcribed by someone else without internalizing their style might provide some short-term benefit but will never set you on the path to your own mastery. Every aspect of a master’s style must be studied in depth. Fewer masters, more depth is more effective than the opposite. With only one father, no wonder we often end up so much like him!

Wishing you and yours a most happy Father’s Day!

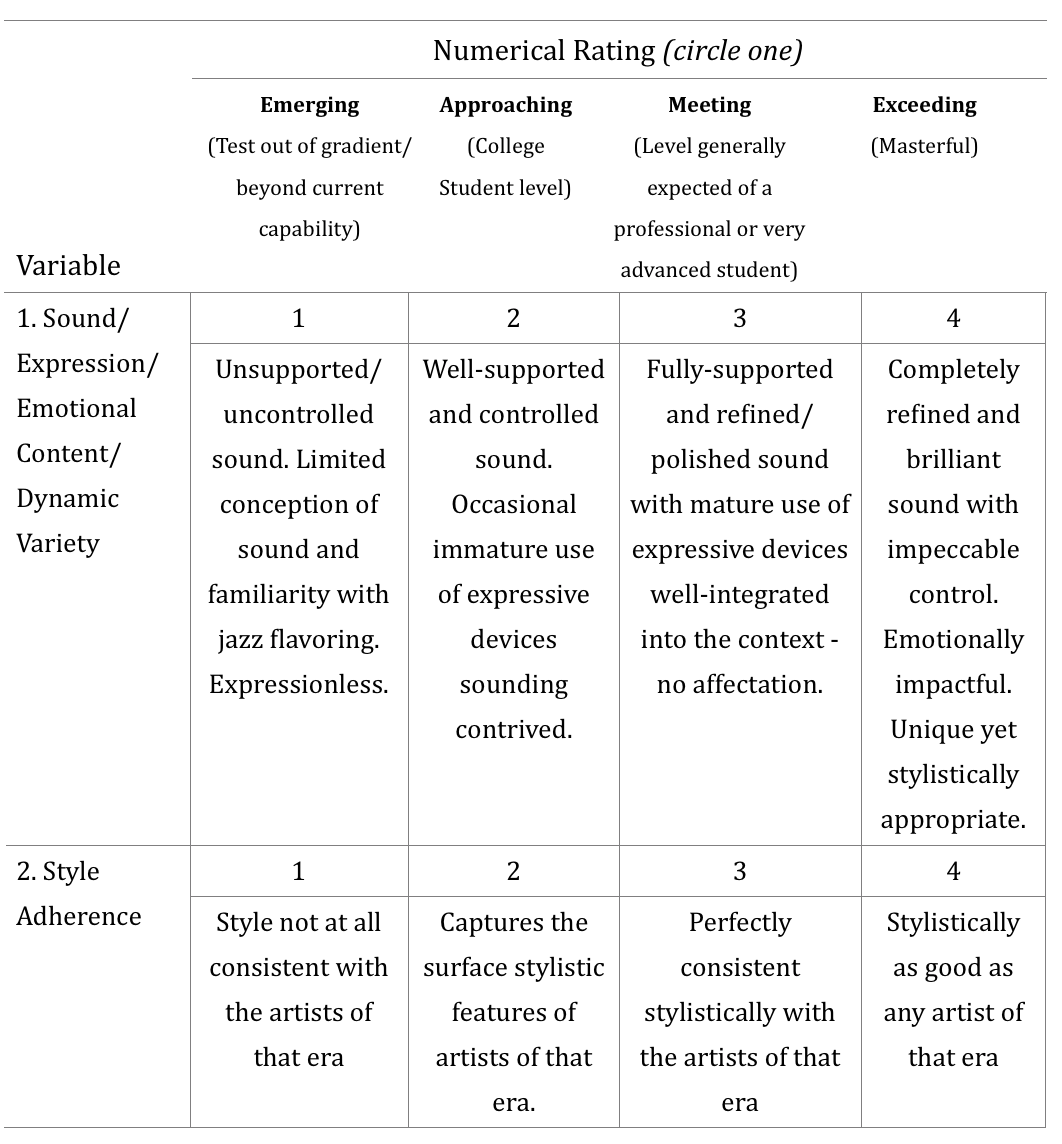

Rubric

Performance Assessment

In other Formative Assessments throughout this Unit, I have scored each chorus of each soloist’s improvisation across the Technical Execution/Fluidity, Time Feel/Rhythmic Variety and Development, and Note Selection/Melodic Construction and Development dimensions on a scale from 1 to 4. This Formative Assessment will focus on the Sound/ Expression dimension and the Style Adherence dimension. Each soloist will get three choruses of each of the following: (1) a Traditional style (2) a Modern style, both of the soloist’s choosing, over a tune of the soloist’s choosing. You may use a rhythm section from the class or, for the more technologically savvy amongst you, the original recording with the soloist muted. The objective is that the student will be able to perform convincingly in both styles, exhibiting all the nuances and characteristics typical of that era.

Traditional styles: Ragtime, Dixieland/Trad. Jazz, Early to Late Swing, Early R&B, etc.

Modern styles: Bebop, Hard Bop, West Coast/Cool, Post Bop, Modal Jazz, Progressive Jazz/Third Stream, Fusion, Contemporary/Smooth Jazz, etc.

The highest chorus score of each solo will be taken for each of the evaluations – (1) and (2). Each soloist will therefore play six total choruses.

Table 1

Improvisation Evaluation Scale: Traditional / Modern Jazz [adapted in part from Smith (2009)]

Comments:

Feedback from Scale Assessment:

3 and above: Exhibits or exemplifies the parameter or characteristic nearly perfectly throughout

2: Exhibits the parameter or characteristic moderately or mostly throughout

1: Does not exhibit the parameter or characteristic to any measurable degree

References

Smith, D. (2009). Development and Validation of a Rating Scale for Wind Jazz Improvisation Performance. Journal of Research in Music Education, 57, 217-235.

Modeling for Independence

JAZZ IMPROVISATION ACROSS TRADITIONAL AND MODERN STYLES: ASSESSMENTS IN A SIX-WEEK UNIT WITHIN A UNIVERSITY-LEVEL JAZZ IMPROVISATION COURSE

PART 3 OF 4: SUMMATIVE ASSESSMENT — IMPROVISATION, TRANSCRIPTION

Ray P. Zepeda

Last month, we entered into a discussion about emulation, both of our fathers and of our jazz mentors, whether consciously or unwittingly. For this third of four installments, I would like to do a deeper dive into specific methods of study of our jazz mentors, namely, the practice of solo transcription and what I call “style” improvisation, and how these might actually enable a developing artist’s independence. Freed from the tyranny of the written page, the performer operates on a tightrope without a net, a Faustian bargain for freedom of artistic expression.

Imagine another situation differing only in matter of degree. You are a twenty-something young man in 1776 Colonial America yearning for freedom from tyranny. What price would you pay to secure it? Would you sign your life away on a piece of paper for all to see all but guaranteeing your being tried and executed for treason? (How many men of any age would do that today?) In August of that year, 56 intrepid men from throughout the Colonies did just that with full knowledge of the potential consequences. While the gamble paid off, forming the basis for the greatest nation in human history, it was one of the greatest leaps of faith ever taken.

The leap of faith we as jazz educators ask of our developing students is not nearly so great, something they should be reflecting on especially during today’s practice session. Moreover, we encourage using “templates” from the masters, transcribing their solos and emulating their performances in every detail. Our Founding Fathers certainly did have some “templates” to go on such as British Common Law, various Parliamentary systems, Judeo-Christian values, and the basic tenets of Western Civilization, but many of the principles upon which our nation was founded were sui generis. While jazz as an artform was created this way, the development of a jazz improviser is rarely ever so. While failure was not an option for our Founders, I encourage you to fail and to do so over and over again.

Wishing you and yours a physically safe and sane Fourth of July!

Rubric

Unit Final Test Performance

As I have done on the Formative Assessments throughout this Unit, I will score each chorus of each soloist’s improvisation across four dimensions on a scale from 1 to 4. Each soloist will get three choruses of each of the following: (1) a Traditional style (2) a Modern style, both of the soloist’s choosing, over a tune of the soloist’s choosing. You may use a rhythm section from the class or, for the more technologically savvy amongst you, the original recording with the soloist muted. Explain why you chose these two styles.

Traditional styles: Ragtime, Dixieland/Trad. Jazz, Early to Late Swing, Early R&B, etc.

Modern styles: Bebop, Hard Bop, West Coast/Cool, Post Bop, Modal Jazz, Progressive Jazz/Third Stream, Fusion, Contemporary/Smooth Jazz, etc.

The highest chorus score of each solo will be taken for each of the evaluations — (1) and (2). Each soloist will therefore play six total choruses. The scores in each of the four dimensions will be averaged to yield a composite score. A composite letter grade translation for reference, roughly speaking, might be:

A: 3 and higher

B: 2

C: 1

Table 1

Improvisation Evaluation Scale: Traditional / Modern Jazz [adapted in part from Smith (2009)]

Comments:

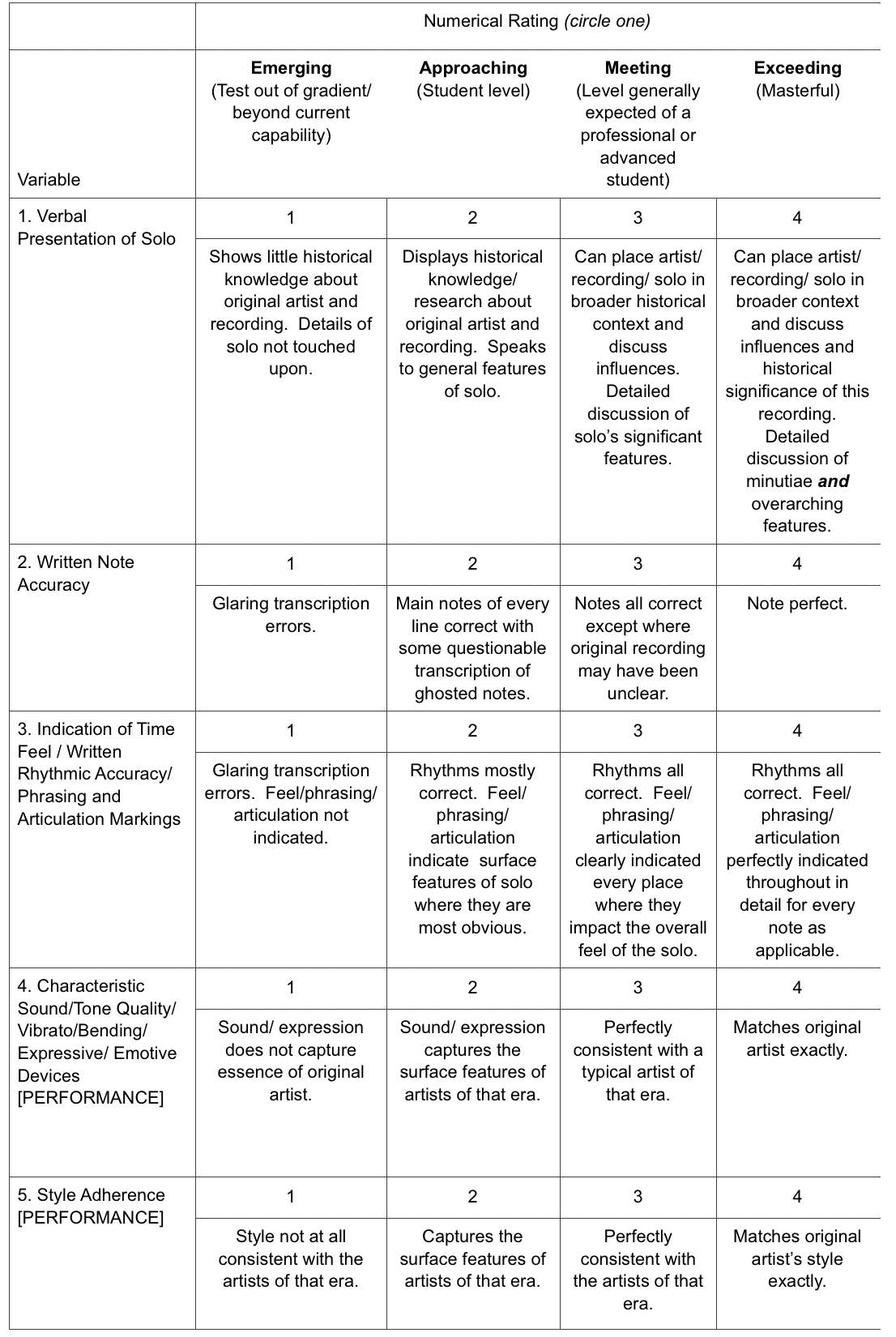

Throughout this 6-week Unit, you have also been working on transcribing by hand one chorus of your choosing from two solos by an artist on your instrument, one from a traditional style and one from a modern style, and practicing to perform it as much like the original artist as possible. I will collect your handwritten transcriptions for grading and will give each student one opportunity to perform each of their two solo transcriptions. Performances are to be a cappella or with the original recording at low volume Your transcriptions and performances will be assessed according to Table 2 below. Explain why you chose these two solos and have your handwritten solo on the overhead for the class to see while you perform it. You will preface your performance with a brief presentation which will include a discussion of your artist and their style highlighting historical details about the original recording and technical details in the solo transcription.

Table 2

Transcription — Notation and Performance Evaluation Scale: Traditional / Modern Jazz [adapted in part from Smith (2009)]

Comments:

Scale Detail for Assessment:

3 above: Exhibits or exemplifies the parameter or characteristic nearly perfectly throughout

2: Exhibits the parameter or characteristic moderately or mostly throughout

1: Does not exhibit the parameter or characteristic to any measurable degree

The scores in each of the five dimensions will be averaged to yield a composite score. A composite letter grade translation for reference, roughly speaking, might be:

A: 3 and higher

B: 2

C: 1

References

Smith, D. (2009). Development and Validation of a Rating Scale for Wind Jazz Improvisation Performance. Journal of Research in Music Education, 57, 217-235.

Happy Birthday, Monsieur Hodges!

JAZZ IMPROVISATION ACROSS TRADITIONAL AND MODERN STYLES: ASSESSMENTS IN A SIX-WEEK UNIT WITHIN A UNIVERSITY-LEVEL JAZZ IMPROVISATION COURSE

PART 4 OF 4: SUMMATIVE ASSESSMENT – FINAL WRITTEN EXAMINATION

Happy Birthday, Monsieur Hodges!

Ray P. Zepeda

Congratulations! You have made it to the fourth and final installment of this Unit. The commitment you have shown to jazz education speaks volumes. The piece you are hearing now is called Elegy, one that I wrote and performed as an homage to Johnny Hodges, born on this day in 1907, whose iconic lead alto sound and solo voice was the distinguishing feature of the Duke Ellington for decades! Too often in jazz education, these masters of the past who can tell a story with just a single note are forgotten in favor of artists of the bebop and subsequent eras. Johnny Hodges, the “Rabbit,” was one such example with his signature portamento, vibrato, and melodic concept.

The opening sections of the Final Examination of this Unit are designed for the student to do well and finish quickly so as to allow adequate time for reflection for the essay portion. Take it yourself and see how you do! I am reminded of the Greek maxim, “…know thyself” and that is exactly the overarching objective of this Unit, hence, the heavier points weighting for the essay section!

Wishing you well in your journey as a jazz educator!

Elegy (for Johnny Hodges)

“Elegy (for Johnny Hodges)” from Raymond Zepeda In Recital – April 11, 1996 by Ray Zepeda.

Examination

Multiple Choice

1) Collective or polyphonic improvisation is most commonly associated with which of the following jazz styles? a) Dixieland b) Ragtime c) Early Swing d) Field Hollers e) Bebop 2) A straight tone or vibratoless sound is most likely to be found in which of the following? jazz styles? a) Early Swing b) Big Band Swing c) West Coast/Cool d) Hard Bop 3) This jazz style is most known to incorporate notions of classical/concert music. a) Classic jazz b) Third Stream c) Contemporary jazz d) Fusion 4) West Coast/Cool saxophonists were more likely to have drawn their influences from which of following from earlier eras? a) Coleman Hawkins b) Johnny Hodges c) Ben Webster d) Lester Young 5) For alto saxophonists, in which of the following jazz styles is the altissimo register most prominently featured during solos? a) Bebop b) Contemporary/Smooth c) Hard Bop d) Progressive 6) Which of the following trumpeters is most known for playing straight eighth notes during improvisation? a) Clifford Brown b) Roy Eldgridge c) Louis Armstrong d) Harry James 7) All of the following are highly characteristic of turnarounds in bebop and later jazz styles from that strain except for? a) Altered-dominant b) Tritone substitution c) Arpeggiated ii-7 chord up to the ninth->#5 of V+7->ninth of I d) Interpolation of half-step-up ii-V before the standard ii-V e) Interpolation of half-step-below ii-V before the standard ii-V 8) Which of the following devices would be the least appropriate or least characteristic of traditional jazz? a) Turns, gruppetti b) Glisses and bends c) Fast vibrato d) Bebop dominant e) Altered dominant 9) During what era were quotes from other tunes first utilized in improvised solos on a regular basis? a) Bebop b) Free Jazz/Avant Garde c) West Coast/Cool d) Smooth jazz/R&B e) Ragtime 10) The following devices were commonly employed by bebop-era drummers behind soloists except for: a) Dropping bombs b) Irregular snare hits c) 4 on the floor d) Ride cymbal pattern on ride or hi-hat e) Melodic interaction with soloists/melody

True-False

11.) “Sheets of sound” in improvisation is common in Big Band swing.

a.) True b.) False

12.) Charlie Parker studied Lester Young who, in turn, studied Frankie Trumbauer

a.) True b.) False

13.) Because the piece uses all of the all-combinatorial hexachords, there is ample room for improvisation in Milton Babbitt’s All Set from 1957 commissioned for the Brandeis Music Festival which, that year, was a jazz festival.

a.) True b.) False

14.) Bebop improvisations feature lines and extensive use of arpeggiation.

a.) True b.) False

15.) Bebop is the first style pre-1950 wherein improvisers and arrangers employed the upper extensions of the chord.

a.) True b.) False

16.) An identifying feature of smooth/contemporary jazz saxophonist, Grover Washington, Jr., is his relaxed phrasing.

a.) True b.) False

17.) Pianist, Oscar Peterson, draws from the bebop, swing, and stride (Art Tatum, James P. Johnson) traditions.

a.) True b.) False

18.) Miles Davis’s bebop-era improvisations are more known for high-register forays than those of fellow bop trumpeter, Dizzy Gillespie.

a.) True b.) False

19.) Ben Webster’s and Coleman Hawkins’s improvisations were generally pure-toned, without subtone and vibrato, especially on ballads.

a.) True b.) False

20.) Use of mutes in trombone improvisations is more characteristic in bebop than in Swing Era big band

a.) True b.) False

Fill In the Blank

21.) A bebop head written over the chord changes of a pre-existing standard is called a(n) __________.

22.) Charlie Parker’s “Scrapple from the Apple” is unique in that it employs the changes to ___________________ in the “A” sections and the changes from ____________________ on the Bridge.

23.) The alto saxophonist from the Cool era whose sound was said to be like a “dry martini” was ____________________.

24.) The sharp and/or flat alteration(s) employed by improvisers on the altered dominant is/are ___________________.

25.) ‘Comping and drumming becomes very sparse or even non-existent behind __________ solos.

26.) The Duke Ellington Orchestra trombonist known for the “yah-yah” effect in his/her solos was _______________.

27.) Switching to 16th notes (from 8th notes) in a solo to add excitement is called _______________.

28.) Ending phrases with two eighth notes, long-short, was commonplace in the __________ era.

29.) Funk licks are most often heard in _______________ jazz solos.

30.) In Latin jazz, solos are played using __________ eighths.

Matching

| _____ 31.) Whole-half diminished scale. | A. Quartal |

| _____ 32.) Building lines and voicings in 4ths and 5ths (as opposed to tertiary harmony) | B. Polychord |

| _____ 33.) B/C | C. ii-7(b5) |

| _____ 34.) Lydian b7 tritone above. | D. V7(b9) |

| E. Pentatonic | |

| F. Slash chord | |

| G. V7 alt. |

Matching

| _____ 35.) Early piano style not originally intended for improvisation but, ultimately, corrupted into “cutting contest” fodder in nightclubs. | A. Count Basie |

| _____ 36.) Artist who defined the standard for “shape” playing in improvised lines in contemporary jazz. | B. Cannonball Adderly |

| _____ 37.) Artist known for extremely sparse but effective solos. | C. Michael Brecker |

| _____ 38.) Bebop with a pinch of blues and pound of soul! | D. Stride |

| E. Dave Brubeck | |

| F. Ragtime |

Short Essay

Essay#1: Describe your own style in historical context. Who are your influences and why have you chosen them as “mentors”? What have you “taken” from each one? Please tell me in your own words based on your own introspection and self-awareness using specific musical terms. Use professional rather than colloquial writing. Limit your response to a half page.

Essay #2: Jazz musicians to this day struggle over John Coltrane’s Giant Steps. Decades before it was written, however, jazz musicians played effortlessly over the bridge of the old standard, Have You Met Miss Jones, which has basically the same changes. Discuss why this struggle persists. Is it only a tempo consideration or does the different style, swing vs. post-bop, have something to do with it? Confine your argument to tempo vs. style and to no more than a page.

Essay #3: Identify at least 3 features you might find in a turnaround on a bebop solo, that of a Swing Era solo, and that of a Dixieland/Trad Jazz solo. Limit your response to one page.

Bird Lives! A Centennial Birthday Rumination for Charlie “Yardbird” Parker

JAZZ IMPROVISATION ACROSS TRADITIONAL AND MODERN STYLES: ASSESSMENTS IN A SIX-WEEK UNIT WITHIN A UNIVERSITY-LEVEL JAZZ IMPROVISATION COURSE

PART 4A OF 4: ANSWER KEY FOR SUMMATIVE ASSESSMENT – FINAL WRITTEN EXAMINATION

Ray P. Zepeda

By popular demand from our readership, I am including an “answer key” highlighting the correct responses for the opening sections of last month’s Final Examination for this Unit. I have purposely not included any helpful hints for the essay portion. I leave that for your own cogitation and self-examination. “…know thyself”!

Along those lines, allow me to take a different tack in this celebration of Bird, born this day 100 years ago. Through the lens of history, jazz educators have often treated Bird as an answer key to a Swing Era music that had run its course while their students have treated the Charlie Parker Omnibook, a compendium of written transcriptions of his most seminal solos, as the answer key to “how to channel Bird.” As with many historical figures who we hold up as geniuses and innovators, Charlie Parker existed at just the right time for his specific intellectual and artistic powers to be most impactful, and he lived long enough, albeit barely, to become bebop’s greatest exponent. (An argument has been advanced that guitarist Charlie Christian, based on his early work with Benny Goodman and others, might have assumed the mantle had he lived long enough). In its defense, the Omnibook does comprehensively present the lexicon of modern jazz’s first era through the eyes of its leading creator, not unlike how the works of Bach do the same for the Baroque era albeit on a smaller scale. (Bebop and hard bop represent our “Common Practice” period, just as the Baroque and Classical eras represent that for concert music). What is important for us as jazz educators, however, is to encourage internalization and not merely rote memorization and regurgitation. The artists’ recordings must be the most important part of the process. Better to learn a solo from the recording than from the written page. The developing improvisor must have tactile familiarity with the mannerisms of a particular style, yes, but adding the ear to the equation is what will solidify it so that these “Birdisms” can be applied elsewhere. Bird studied Lester “Prez” Young which is largely why his solos maintain so much lyricism at even impossibly fast tempos. Coming from Kansas City, he internalized the players around him which is why his playing is so deeply rooted in the blues even over complicated chord changes. His written practice material was comprised of method and etude books, not solo transcriptions. The latter were learned from 78 rpm records, weighting the tone arm as necessary to slow down the most rapid passages. Moreover, Bird was purported to have practiced 14 hours a day for 3 or 4 of his formative years.

So, here’s to another century of basking in and learning from Bird’s recorded output and that of all who have followed and who undoubtedly will follow him! All roads to jazz modernism must go through Bird and this roadmap is unlikely to change over the next hundred years either. Now how’s that for a sphere of influence?

Bird lives!

Examination

Multiple Choice

1) Collective or polyphonic improvisation is most commonly associated with which of the following jazz styles? a) Dixieland b) Ragtime c) Early Swing d) Field Hollers e) Bebop 2) A straight tone or vibratoless sound is most likely to be found in which of the following jazz styles? a) Early Swing b) Big Band Swing c) West Coast/Cool d) Hard Bop 3) This jazz style is most known to incorporate notions of classical/concert music. a) Classic jazz b) Third Stream c) Contemporary jazz d) Fusion 4) West Coast/Cool saxophonists were more likely to have drawn their influences from which of following from earlier eras? a) Coleman Hawkins b) Johnny Hodges c) Ben Webster d) Lester Young 5) For alto saxophonists, in which of the following jazz styles is the altissimo register most prominently featured during solos? a) Bebop b) Contemporary/Smooth c) Hard Bop d) Progressive 6) Which of the following trumpeters is most known for playing straight eighth notes during improvisation? a) Clifford Brown b) Roy Eldgridge c) Louis Armstrong d) Harry James 7) All of the following are highly characteristic of turnarounds in bebop and later jazz styles from that strain except for? a) Altered-dominant b) Tritone substitution c) Arpeggiated ii-7 chord up to the ninth->#5 of V+7->ninth of I d) Interpolation of half-step-up ii-V before the standard ii-V e) Interpolation of half-step-below ii-V before the standard ii-V 8) Which of the following devices would be the least appropriate or least characteristic of traditional jazz? a) Turns, gruppetti b) Glisses and bends c) Fast vibrato d) Bebop dominant e) Altered dominant 9) During what era were quotes from other tunes first utilized in improvised solos on a regular basis? a) Bebop b) Free Jazz/Avant Garde c) West Coast/Cool d) Smooth jazz/R&B e) Ragtime 10) The following devices were commonly employed by bebop-era drummers behind soloists except for: a) Dropping bombs b) Irregular snare hits c) 4 on the floor d) Ride cymbal pattern on ride or hi-hat e) Melodic interaction with soloists/melody

True-False

11) “Sheets of sound” in improvisation is common in Big Band swing.

a.) True b.) False

12) Charlie Parker studied Lester Young who, in turn, studied Frankie Trumbauer

a.) True b.) False

13) Because the piece uses all of the all-combinatorial hexachords, there is ample room for improvisation in Milton Babbitt’s All Set from 1957 commissioned for the Brandeis Music Festival which, that year, was a jazz festival.

a.) True b.) False

14) Bebop improvisations feature lines and extensive use of arpeggiation.

a.) True b.) False

15) Bebop is the first style pre-1950 wherein improvisers and arrangers employed the upper extensions of the chord.

a.) True b.) False

16) An identifying feature of smooth/contemporary jazz saxophonist, Grover Washington, Jr., is his relaxed phrasing.

a.) True b.) False

17) Pianist, Oscar Peterson, draws from the bebop, swing, and stride (Art Tatum, James P. Johnson) traditions.

a.) True b.) False

18) Miles Davis’s bebop-era improvisations are more known for high-register forays than those of fellow bop trumpeter, Dizzy Gillespie.

a.) True b.) False

19) Ben Webster’s and Coleman Hawkins’s improvisations were generally pure-toned, without subtone and vibrato, especially on ballads.

a.) True b.) False

20) Use of mutes in trombone improvisations is more characteristic in bebop than in Swing Era big band

a.) True b.) False

Fill In the Blank

21) A bebop head written over the chord changes of a pre-existing standard is called a(n) Contrafact.

22) Charlie Parker’s “Scrapple from the Apple” is unique in that it employs the changes to “Honeysuckle Rose” in the “A” sections and the changes from “I Got Rhythm” on the Bridge.

23) The alto saxophonist from the Cool era whose sound was said to be like a “dry martini” was Paul Desmond.

24) The sharp and/or flat alteration(s) employed by improvisers on the altered dominant is/are b9, #9, b5, and #5.

25) ‘Comping and drumming becomes very sparse or even non-existent behind bass solos.

26) The Duke Ellington Orchestra trombonist known for the “yah-yah” effect in his/her solos was “Tricky Sam” Nanton.

27) Switching to 16th notes (from 8th notes) in a solo to add excitement is called double time (or double-timing).

28) Ending phrases with two eighth notes, long-short, was commonplace in the bebop era.

29) Funk licks are most often heard in contemporary/smooth jazz solos.

30) In Latin jazz, solos are played using straight eighths.

Matching

| C 31) Whole-half diminished scale. | A. Quartal |

| A 32) Building lines and voicings in 4ths and 5ths (as opposed to tertiary harmony) | B. Polychord |

| F 33) B/C | C. ii-7(b5) |

| G 34) Lydian b7 tritone above. | D. V7(b9) |

| E. Pentatonic | |

| F. Slash chord | |

| G. V7 alt. |

Matching

| F 35) Early piano style not originally intended for improvisation but, ultimately, corrupted into “cutting contest” fodder in nightclubs. | A. Count Basie |

| C 36) Artist who defined the standard for “shape” playing in improvised lines in contemporary jazz. | B. Cannonball Adderly |

| A 37) Artist known for extremely sparse but effective solos. | C. Michael Brecker |

| B 38) Bebop with a pinch of blues and pound of soul! | D. Stride |

| E. Dave Brubeck | |

| F. Ragtime |

Short Essay

Essay#1: Describe your own style in historical context. Who are your influences and why have you chosen them as “mentors”? What have you “taken” from each one? Please tell me in your own words based on your own introspection and self-awareness using specific musical terms. Use professional rather than colloquial writing. Limit your response to a half page.

Essay #2: Jazz musicians to this day struggle over John Coltrane’s Giant Steps. Decades before it was written, however, jazz musicians played effortlessly over the bridge of the old standard, Have You Met Miss Jones, which has basically the same changes. Discuss why this struggle persists. Is it only a tempo consideration or does the different style, swing vs. post-bop, have something to do with it? Confine your argument to tempo vs. style and to no more than a page.

Essay #3: Identify at least 3 features you might find in a turnaround on a bebop solo, that of a Swing Era solo, and that of a Dixieland/Trad Jazz solo. Limit your response to one page.

Ruminations on Music Education and the “Edge Effect”

My earliest clear memories of the art of music making are of my grandfather, Lamberto “Chapo” Cortez Zepeda, playing mostly Mexican traditional folksong repertoire on his violin either solo or in a trio configuration. Born in Arizona before it was a State – the joke was always that we didn’t cross the border, the border crossed us – he took violin lessons from the local barber in order to get out of saying the Rosary and, by his teens, he memorized all the songs that the local band played at dances, baptisms, and concerts. His mother, acting as his agent and surprisingly nonplussed that he had eschewed Catholic religiosity for music, approached the bandleader, himself a piano player for the silent movies, and demanded that Chapo be added to the orchestra without an audition. Chapo ended up auditioning for him anyway and, thoroughly impressed, he hired him on the spot. The orchestra worked so much that, coupled with his job working for a local Chinese grocer, he was expelled from high school. The point is that Chapo received his education in the arts on the street which, at the time, was the only way one could obtain it in most of America, let alone in a small, Mexican copper mining town.

Too often, stories like my grandfather’s are romanticized and put forth as the “true” musical education while formal education is downplayed. This is most often the case with jazz and popular music where the literati claim that the music suffered when the training left the bandstand and retreated into the academy causing critics to lament the institutionalization of the art. Having learned both on the streets of Los Angeles and in academic settings, I can say that such claims are exaggerated and not evidence-based. In fact, the two methods reinforce each other despite the inherent limitations of each though I believe the balance leans towards the former based on my personal experience and that of my colleagues throughout a long career amassing some 50 professional recording credits this decade alone including two commercially-released albums of my own. (My early violin education by observation of Chapo playing and my immersion in the listening-oriented Suzuki string program no doubt contribute towards this belief but it can be mostly attributed to my trial-by-fire introduction to the professional jazz world as a saxophonist at age 15 and forced, on-the-spot thinking in many a recording session!) These are among the problems I have set out to grapple with. What is the right educational balance to achieve maximum artistic and career success? Does the answer lie not only the study of music education but also in the analysis of the training in other creative arts both formal and informal, both performing and visual? Is there a common thread of how successful practitioners across all artistic fields do what they do and why they do it? Are case studies the most efficacious method of finding these answers and how will these answers from the arts contribute to the overall educational experience? What then are the implications of an arts-enlightened education for the broader society and to what extent can the devaluation of music be attributed to the lack of it?

Having studied music education formally at the graduate level over the last year and a half, I can see that relying on such a limited focus to provide these answers does not hold much promise. Rather, it was my business-oriented classes around the arts that exposed me to the “Edge Effect” that disciplines have on each other, both across artistic fields and between creative and commercial collaborators, to produce an optimized result. Could this Edge Effect that exists between artistic disciplines provide answers to the questions posed? Rather than in a specialized fine arts program, the best laboratory for such investigation is likely to exist in a program where practitioners from disparate artistic endeavors are brought together to learn from and teach each other. Outside perspectives thusly gained will more deeply inform one’s own practice of their native art form. As I have seen gig pay not increase appreciably since the early 1980s and album sales revenue rapidly become nonexistent, I am motivated to work in stalwart fashion through educational reform to reverse the continual reduction in the value of music.